Being what we see

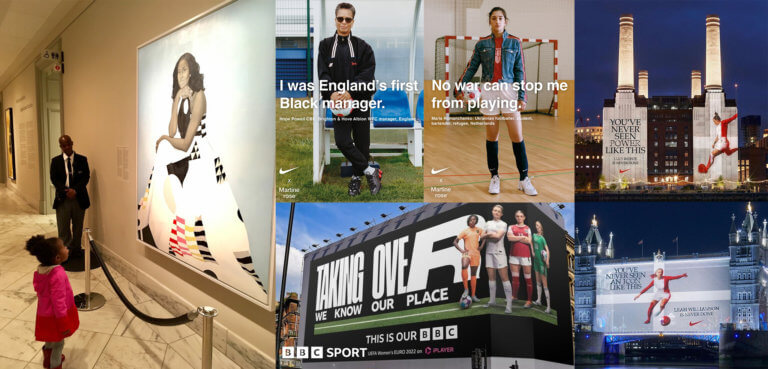

Two year-old Parker Curry stood in front of Amy Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama, ignoring her mums pleas to spin around for a photo. To her side, a visitor from out of town had noticed the little girl gazing up with her mouth wide at the painting, snapped a quick photo and uploaded it to Facebook. By the next morning the photo had gone viral. Thousands of people liked, retweeted, and shared the image across the World, even drawing the attention of Obama who reacted with a slew of heart-eyed emojis.

One of the phrases that appeared time and again, beneath the many copies of the image, was “You can’t be what you can’t see”, an expression that’s resurfaced again recently with the beginning of the UEFA Women’s Euro football tournament taking place across England.

The history of women in sport is a turbulent one. At the end of the 1914/15 season, the Football League was forced to suspend all of its matches due to WW1. Whilst women’s participation in football was already long established up to this point, it had never been as popular as it was about to be, as young British men and boys were sent off to fight leaving the women behind, with many taking up positions in factories around the country. These workers often passed their lunch breaks having a kick-about, which gradually turned into formal teams playing matches to raise money for the war effort. With entertainment becoming of national importance to take the mind off what was happening on the continent, more and more people took interest, with matches regularly seeing crowds of tens of thousands of people.

According to the BBC, a Boxing Day match at Goodison Park attracted 53,000 spectators, with a further 14,000 locked outside trying to get in. This was 1920, and while the nation had been ravaged by war it was slowly beginning to put itself back together. The men who returned slowly took the positions of the women who had replaced them on the assembly line, breaking up the friendships and bonds that had created those teams in the first place. In a further devastating move, the Football Association agreed in 1921 that all its clubs must refuse the use of their stadiums and pitches to women’s football teams, citing strong opinions from doctors and other professionals who suggested football was a most unsuitable sport for females.

Whilst efforts were made by several teams to continue, with Lily Parr becoming one of the goalscoring greats in English history with over 1,000 goals across a 30-plus year career, access to the game dwindled over the next five decades, with the ban not being lifted until 1971.

Clockwise from left: Parker Curry looks at Michelle Obama; Martine Rose x Nike – Hope Powell; Martine Rose x Nike – Maria Romanchenko; Nike – Lucy Bronze, Battersea Power Station; Nike – Leah Williamson, Tower Bridge; We Know Our Place, BBC Creative

If 1921 was a sudden death for women playing football in Britain, a slow resurrection started to take shape over the subsequent decades, culminating in what many people are now calling a golden age for women in sport, kicking off with the landmark 2012 London Olympics, the first time every country had a female athlete in their team after Saudi Arabia lifted their ban on women competing.

The milestones have kept on coming since. Serena Williams won the Australian Open in 2017 whilst two months pregnant. Megan Rapinoe won the World Cup and stood up to an entire sporting federation to ensure that the US Women’s National Team is paid equally to the Men’s. Simone Biles became the greatest gymnast of all time, whilst simultaneously reminding everyone that it’s OK to admit, on the World stage, that you’re pulling out of an event for mental health reasons. Katie Taylor had a worldwide audience of 1.5 million people watch her fight against Amanda Serrano at Madison Square Garden, a fight that had to be moved into “the big room” due to too many tickets being sold. I watched grown Scottish men cheer on the United States against England in the Women’s World Cup 2019, in a village pub somewhere with a population of about 100 people.

So with the golden age hopefully upon us, the design world is helping to push this momentum forward. To trail the massive summer of sport on the BBC, their in-house team made the “We Know Our Place” campaign. Launched during the Women’s FA Cup final, it challenges the idea that “women should know their place”, highlighting the passion, dedication and success that shapes young girls into famous athletes.

In the world of fashion, Martine Rose has teamed up with Nike to create a limited edition range of Shox, launched with a powerful campaign featuring nine women from all over Europe, whose love and commitment to football is undeniable, such as Hope Powell CBE (England’s first black manager) to Maria Romanchenko, a refugee who was playing in Ukraine’s first division.

For the start of the Women’s Euro football tournament, Nike celebrated by projecting members of the England team onto London monuments that reflect their footballing characteristics and status, such as “defence”, “iconic” and “power”.

So if the adage that “you can’t be what you can’t see” is true, then the creative industry is certainly making a fine attempt of helping to tackle the latter, and I for one can’t wait to see what the Lionesses can do this summer.

Written by Harry Smith, Senior Designer

Enjoyed this article? We also post our articles on LinkedIn. Follow us to stay up to date.

Follow us on LinkedIn